The Managers' Guide № 127

Master engineering leadership with essential insights on handling toxic top performers, splitting bloated teams, and breaking the false consensus effect. Plus, learn why avoiding negativity echo chambers is the ultimate career hack

DIET DAY 1

I have removed all the bad food from my home.

It was delicious.

DocAtCDI

False Consensus: Why We Think We're The Baseline

- 🧠 The bias of assumed alignment — The article explores the False Consensus Effect, a cognitive bias where we tend to overestimate how much others share our beliefs, behaviors, and opinions. We assume our internal narrative is the “normal” one, leading us to believe that the majority agrees with us, even when they don’t.

- 🙊 Silence does not mean yes — A major pitfall for leaders is interpreting a lack of pushback as agreement. The author warns that just because a room is quiet, it doesn't mean consensus has been reached — often, team members are simply hesitant to speak up against a perceived majority or authority figure.

- 🔍 Why it happens — This bias stems from the availability heuristic (our own thoughts are most available to us) and our tendency to associate with similar people. This creates an echo chamber where we constantly validate our own views, making us blind to alternative perspectives.

- 🛠️ Tactics to break the illusion — To combat this, leaders need to shift their approach. Strategies include: speaking last so you don’t anchor the team to your opinion, assigning a “Devil’s Advocate” to force distinct viewpoints, and utilizing anonymous voting to reveal the true distribution of opinions without social pressure.

- ❓ Seek disconfirmation, not validation — Instead of asking “Does everyone agree?”, leaders should ask questions that invite friction, such as “What are we missing?” or “Who sees this differently?” — actively hunting for the disagreement that usually remains hidden.

Career advice, or something like it

- 🚫 Beware the trap of cynical bonding — Every workplace has "watering holes" where the jaded hang out. These groups feel inviting because complaining is an easy way to bond, but they create a trap: you are only accepted as long as you are cynical. If you are ambitious or optimistic, you are implicitly excluded.

- 🛑 The 20% rule — The author suggests a strict personal limit for engagement: if a community or chat channel is more than 20% negative, leave it. Staying in these environments is bad for your career and your mental health, even — or especially — if the complaints resonate with you.

- 🛣️ Fix it or forget it — Instead of whining, choose one of two productive paths. Either focus your energy on "making things better" to advance your career, or simply do your job and save your energy for your family and hobbies. Venting in private groups changes nothing and only fuels sadness and anger.

- 🏆 Success leaves clues — A key observation is that the most admirable people in the industry are never found in the

#everything-suckschannels. High performers recognize when things are broken, but they choose to "either fix it or accept it" rather than wasting time complaining about the past. - 🛡️ Protect your community — Negativity works like a virus; if a community becomes a negativity echo chamber, the "good folks will disengage" and find better places to be. To save a community you love, you have to actively model positive behavior and moderate the tone before the cynics drive the interesting people away.

How to Deal With a Toxic Top-Performer

- ☣️ The most dangerous employee — The article defines the “Toxic Top Performer” (often called a Brilliant Jerk) as someone who delivers exceptional results but destroys the team environment. The author argues this is the most difficult management challenge because leaders fear that firing them will hurt the business, creating a paralysis that damages culture.

- 📊 The Performance-Values Matrix — To objectively assess your team, Bailey suggests mapping employees on a 2x2 grid of Performance vs. Values. While we all know what to do with low performers, the High Performance / Low Values quadrant is critical: these individuals are not assets; they are cultural liabilities that must be managed out or corrected immediately.

- 📉 Culture is what you tolerate — By keeping a toxic high performer, a leader implicitly tells the rest of the company that revenue or code is more important than respect and teamwork. The article emphasizes that “the standard you walk past is the standard you accept,” and tolerating bad behavior encourages the rest of the team to act poorly or simply leave.

- 🗣️ Shift the feedback focus — Managers often fail to correct these employees because performance reviews focus on what was achieved, not how. To fix this, you must give feedback specifically on values and behavior, making it clear that a lack of soft skills or teamwork acts as a cap on their seniority and compensation.

- 🌤️ The “relief” phenomenon — The author observes that leaders often agonize for months about firing a key revenue generator or lead engineer. However, almost universally, once the toxic person is gone, the team reacts with immediate relief, and overall productivity actually increases because the emotional drag on the group has been removed.

Mistakes you shouldn’t let your reports make

- 🛑 The difference between learning and damage — The author distinguishes between "good mistakes" (which help a new manager learn) and "fatal mistakes" (which damage the team or product permanently). A manager's manager should let the former happen but must actively step in to prevent the latter.

- 💻 Stop writing code — The most common trap for new engineering managers is holding onto coding tasks. The author argues you must let go of the "critical path." If you are coding, you are likely becoming a bottleneck for the team and, more importantly, you are using it as an escape mechanism to avoid the harder work of managing people.

- 🗓️ 1:1s are not optional — Skipping one-on-ones or turning them into status updates is a major failure. These meetings are the "primary interface" for management. If you don't hold them consistently, you lose the ability to detect burnout, align on goals, and build the trust required to lead effectively.

- ⛱️ Don’t be an umbrella — Many managers try to "shield" their team from all company politics and organizational chaos. This is a mistake. If you block all the noise, your team lacks the context they need to make smart trade-offs. You should act as a filter or a lens, not a solid wall that keeps them in the dark.

- 💣 No surprises in reviews — It is a catastrophic failure if a team member is surprised by their performance review. Feedback must be continuous and immediate. If you save up negative feedback for the official review cycle, you have failed to give them a chance to correct course, which is unfair and demotivating.

- 🐢 Waiting too long to fire — New managers often hope that underperformance is a temporary blip or that they can "coach" a bad fit into a good one. The article warns that waiting too long to let someone go drags down the entire team’s morale and velocity. You cannot save everyone.

When a team is too big

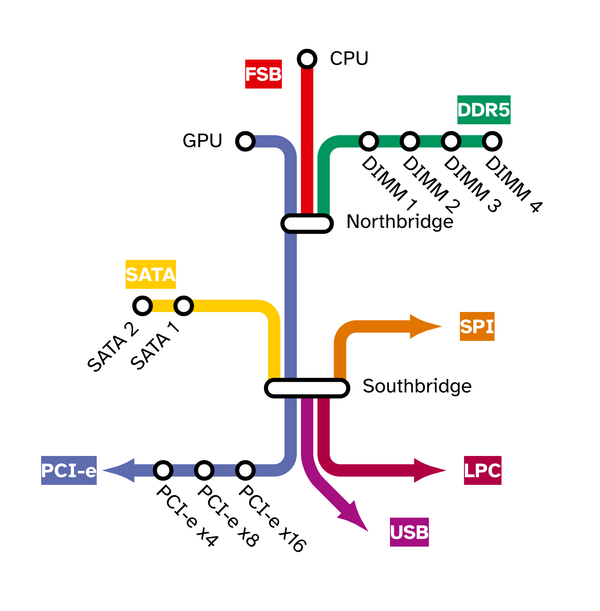

- 🗣️ The Communication Explosion — The main drag on large teams isn't the work itself, but the "communication tax." The number of communication lines grows quadratically ($N(N-1)/2$), not linearly. The author notes that adding a single person to a large team adds disproportionately more noise than value, eventually consuming all productive time in alignment meetings.

- 📉 The Ringelmann Effect — The article highlights a psychological phenomenon known as "social loafing," where individual effort actually decreases as the group size increases. In large teams, ownership becomes diluted, leading to the bystander effect where everyone assumes “someone else” is handling the critical issues.

- 🐌 Symptoms of the "Bloat" — Ewerlöf lists specific red flags that indicate your team has crossed the threshold: Standups act as boring status reports where most people are tuned out, decisions take weeks to reach consensus, and team members no longer possess a shared mental model of the codebase.

- 🧠 Cognitive Load is the limit — A team should be small enough that every member can reasonably understand the scope of their collective work. The author implies a reverse-Conway’s Law: "if the team is too big, the software architecture probably is too." A bloated team usually indicates a monolithic architecture that lacks clear boundaries.

- ✂️ Mitosis: How to split — The solution is to split the team (Mitosis), but the cut line is critical. You should never split horizontally (e.g., "Frontend Team" vs "Backend Team") because this increases dependencies. Instead, split vertically by business domain or user journey to ensure the new, smaller squads remain autonomous and fast.

Happy Holidays, folks! I'll be back in January.

That’s all for this week’s edition

I hope you liked it, and you’ve learned something — if you did, don’t forget to give a thumbs-up, add your thoughts as comments, and share this issue with your friends and network.

See you all next week 👋

Oh, and if someone forwarded this email to you, sign up if you found it useful 👇